Background

Since the origin of the idea of attention (Bahdanau et al., 2015), it has become a norm to try to insert it in a seq2seq model, especially in translations. It is such an intuitive and powerful idea (not to mention the added benefit of peaking into an otherwise blackbox model) that many tutorials and blog posts made it sound like one should not even bother with a model without it as the results would for sure be inferior. (Truthfully, even working on my own post on this topic earlier, I completely skipped the simpler approach too.) However, is it really the case? Does the added complexity introduced by an extra layer really translate into a significantly superior performance? In this post, I set off to construct a controlled experiment to estimate the exact benefit of using attentions in a seq2seq-based translation model.

Before going into the details of the case study, it is worth emphasizing that there is really no general answer or silver bullet to the above question as there are just too many factors that can change the results (e.g., the dataset, the model architecture, just to name a few). Hence, such questions should always be evaluated on a case-by-case basis and the goal of this post is by no means to offer any general advice. Rather, the goal is to show the importance of experimentation and of always starting with a baseline.

In the following sections, I’ll describe the key components of the models used in the experiment and present the results in the end. My complete code for this project is hosted here.

Data

Ideally, to make the study useful, I should run the experiment on a variety of datasets and report the results for all of them. However, due to time constraint, I have only tested it on one parallel English-French dataset provided by the Tatoeba Project. The dataset originally have 155K bilingual pairs. After removing duplicate pairs and limiting to sentences that are shorter than 20 tokens (by removing less than 1% of the data), I ended up with 154K pairs.

At this point, I noticed that there are two interesting “traps” in the data.1 First, there are far more duplicate English sentences than duplicate French. In particular, 95% of the French sentences are unique but only 70% of English are. Based on my spot check, this is mainly due to the more complex verb conjugations in French than in English. For example, simply translating the sentence “run!” to French doubles the sample size as one can say either “cours !” or “courez !”. This interesting linguistic phenomenon influenced my decision whether I should train an English-to-French translator or vice versa. If I had gone with the former, I would have risked making the model harder to learn because the same input can be mapped to different outputs, which is not a big problem if I have enough data but it’s not my case here. Hence, in the end, I went with translating French to English to minimize the risk, which also makes the human evaluations easier.2

Another “trap” is that the dataset contains many recurring themes. For example, there is a big cluster of sentences that teaches users to say “you’d better go” in various situations, ranging from simply “you’d better go”, “I think you’d better go”, to “it’s getting dark. you’d better go home.” If the model learns enough of them in the training data, it is perhaps too easy for it to translate its variations in the test set, which makes us prone to overestimate its ability to generalize to the unseen data. In other words, we have a data leakage problem here (although not as serious as having the exact same copy of input and output in both training and testing). One way to minimize the risk is splitting the data based on the unique clusters so that sentences from the same cluster cannot appear in both training and testing. Once again, due to time constraint, I did not do any of that.3 Instead, I simply split the data based on the unique English sentences, which essentially “clusters” the data based on the exact string matching. Why English not French? This is because there are more duplicates in English so I’m more likely to capture the high-level clusters by splitting on them. Obviously, this did not solve the “you’d better go” problem described earlier where the sentences are not exact duplicates and can still appear in both sets. Yeah, that’s true.

Lastly, keeping all tokens in the training data, I have an English vocabulary of 13K tokens and a French one of 22K. The tokenizations were done using the English and French tokenizers provided by spaCy.

Models

To make sure the results are comparable, I created two models with the exact same architecture with the only difference being an extra attention layer in one of them. Specifically,

The encoders in both cases are exactly the same (although trained separately). Simply put, each embedded input token from the source language (i.e., French) is processed by a single-layer, unidirectional LSTM with a hidden size of 256.

In the model without attention, the decoder is just another single-layer, unidirectional LSTM (also of size 256) that takes its initial states from the encoder final states and, in a teacher-forcing fashion, takes its input from the embedded true target (i.e., English).

In the model with attention, at each decoding step, the decoder consults an extra attention layer that computes a weighted average of the encoder outputs at all timesteps (with the weight representing the amount of “attention” the decoder should pay to each of them, respectively) and combines that with the current decoder input to generate a prediction. Theoretically, in doing so, instead of cramming all encoded information into the initial states, the decoder has access to all of them at all times, and in an intelligent fashion. In particular, the attention layer I implemented in this experiment is exactly the same as the one I described in my previous post. Aside from this extra layer, the decoder is also a single-layer unidirection LSTM, trained with teacher-forcing.

Both the source’s and the target’s embedding layers are initialized by the fasttext embeddings in the respective languages. Based on my experiment, using these pre-trained embeddings doesn’t do much to decrease the validation loss but makes it easier for the attention layer to find the right place to attend. In terms of model size, both models have about 15M parameters, of which 70% come from the two embedding layers. The one with attention has 100K more parameters.

Training

Both models were trained using the Adam optimizer and early stopping that was monitored on the validation cross-entropy loss. In both models, it took 6-7 epochs to see the validation loss plateau. On a per-epoch basis, the one with attention took almost twice as long to run.

Results

The results from the two models are first evaluated quantitatively using the BLEU score, which essentially measures the amount of overlaps of n-grams between the actual and predicted translations. The results, computed using 4-grams, are shown below (on a scale of 0-1):4

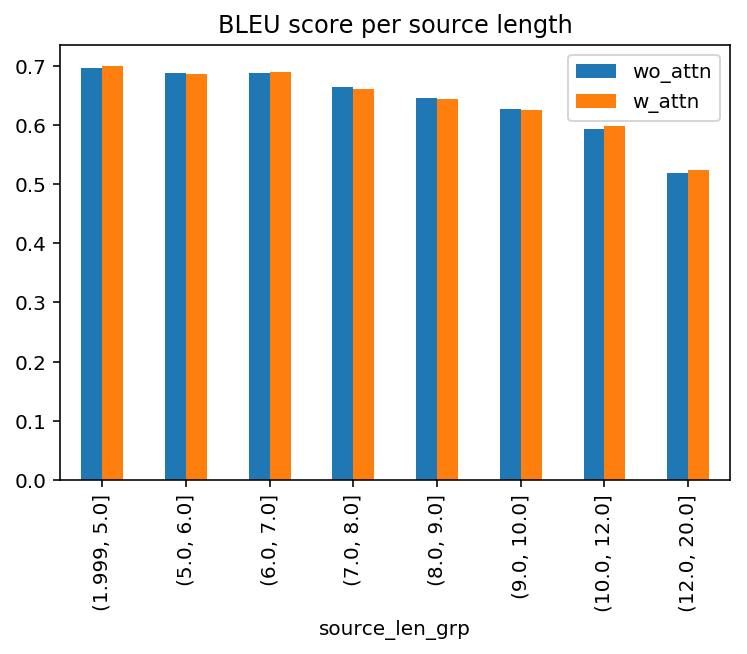

It looks like, in aggregate, the model with attention led to an only slightly higher BLEU score. But given the benefit of attention, did it do noticeably better with long sentences? To test the hypothesis, I grouped the sentence pairs by the source length and re-computed the scores per group below:

Again, the “uplift” is rather underwhelming. In the longest sentence group above (13-20 tokens), the uplift is only 1% relatively.

But is BLEU really a good metric? Yes, it’s useful as a scalable quantitative measure but n-gram overlaps don’t always translate directly into translation quality. To get a better sense, it is often necessary to review some of the translations manually, and this is where my expert French skills come to shine! In particular, I reviewed 100 randomly sampled predictions from the two models and compared them with the source and the actual target to determine whether they are good or not. In the table below, I present my results in the last two columns (1 if a translation is considered good):

In aggregate, the predictions from the no-attention model are deemed good 37% of the time and those from the attention model are good 41%. The difference is not statistically significant (p-value = 0.66), which shows that the added attention layer, once again, did not significantly improve the translation quality.

While reviewing these translations myself, I noticed the notorious “hallucination” problem that plagues the image caption models where the model generates pieces of information that are not present in the source. For example, in the 7th example above, the correct translation is “what’s your favorite word?” but neither predictions got the “word” correct and decided to completely invent something new that did not exist in the source sentence (one says “type” and the other says “song”). This phenomenon is likely due to bias in the language priors (the decoder is a language model after all), which makes me wonder whether those pre-trained language models, despite having been shown to significantly improve many downstream tasks, can potentially exacerbate this particular problem.

Furthermore, I suspect many of the perfect translations are in fact at least partially due to the data leakage problem described in the beginning and cannot be attributed to the model itself. In the cases where an input sentence, along with all of its variations, has never been seen in the training data, the model usually falls apart and generates something that is completely irrelevant.

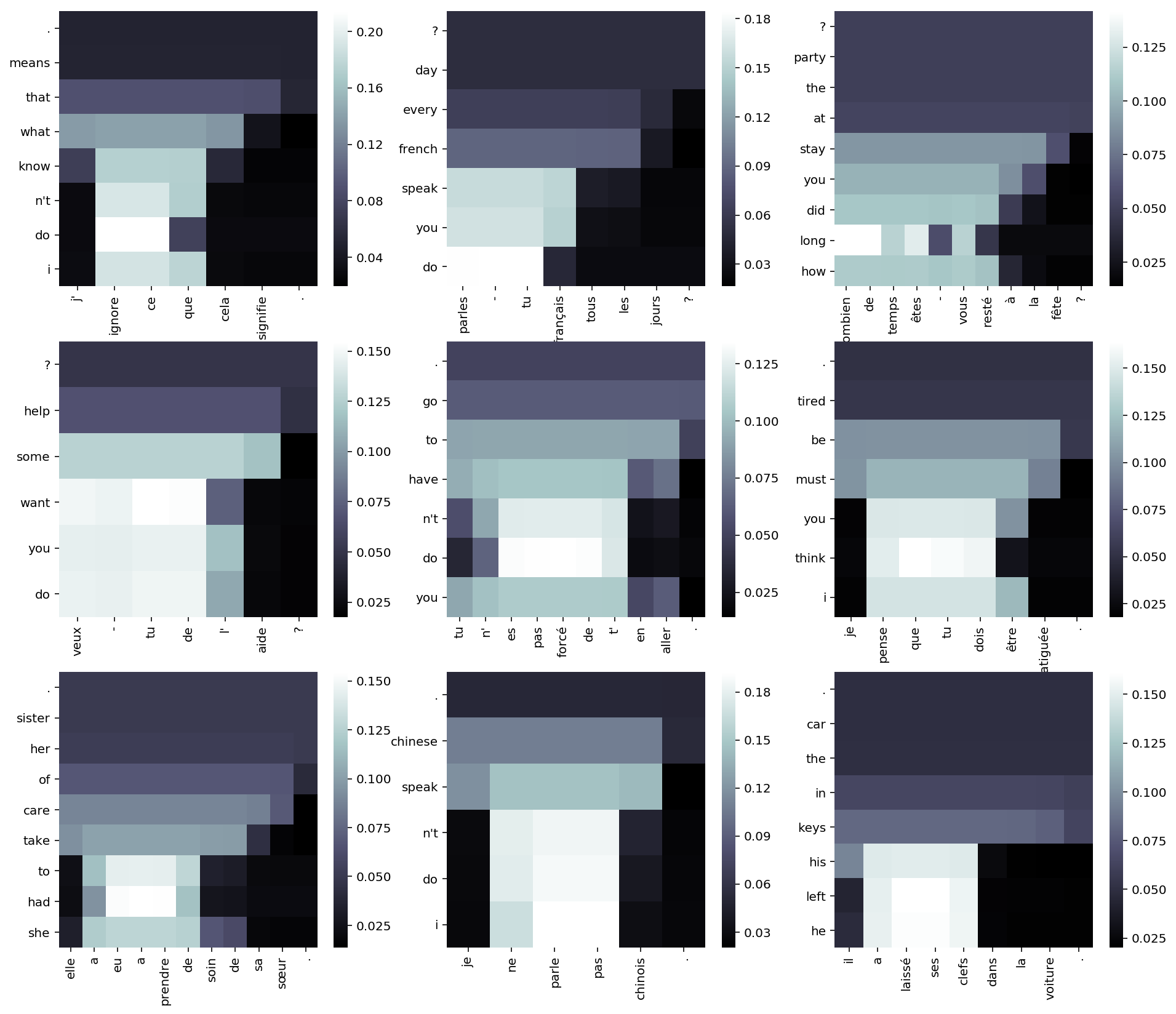

Comparisons aside, I was also curious to see whether the learned attention weights could show that the decoder was at least paying attention to the “right” places from the encoder outputs. To get an idea visually, I randomly sampled 9 translations that match the true target exactly and visualized their attention weights below. (The horizontal axis is the source and the vertical is the target. The whiter a cell is, the heavier its attention weight is.) After seeing the results, I can only say… well, kind of.

First of all, as shown above, unlike the crisp, precise pattern shown in the original paper, my attention weights are often spreaded out horizontally, meaning that the decoder did not have a good idea where to look at exactly. For example, in the first plot above, when generating “do”, “n’t”, and “know”, theoretically the decoder just needs to pay attention to the input “ignore” but in reality, it also consults a couple irrelevant words afterwards. There are also misalignment. In the same plot, when outputting “i”, the decoder completely ignores the corresponding input “j’” and skips forward instead. Secondly, the attention weights usually fade out as the decoding timestep increases (i.e., as we move up vertically in the matrix). This is worrisome because it implies that the translations at the later timesteps received little help from the attention layer, which is ironically what the layer is for in the first place. Hence, all things considered, despite increasing the model size and making the training step longer, the attention layer in this case was still under-trained and did not offer too much help in the end.😔

Conclusion

In this project, I tried to estimate the effect of the attention layer in a seq2seq translation model by performing a simple controlled experiment. After having compared the BLEU scores, manually reviewed a sample of the results, and visualized the learned attention weights, I unfortunately did not find any evidence suggesting any added benefit from the extra layer.

That said, as mentioned in the beginning of this post, a big caveat of this study is that the above results are based on this particular dataset and these particular model architectures only. For example, the way I implemented the attention layer is only one of the many ways of doing so and there are many other approaches out there ranging from simple dot products between the previous hidden state and each of the encoder outputs to this rather peculiar way of only using the previous hidden state and the current decoder input as implemented in this PyTorch tutorial.5 Hence, without experimenting with any alternative architectures (or tuning the various hyperparameters), the goal of this project is not at all to say an attention layer is not necessary. Rather, my goal is simply to urge practitioners to always build a solid, albeit boring, baseline first before venturing into a much more complicated solution. What you find may very well surprise you, as it did here for me.🙂

References

Bahdanau, D., Cho, K., & Bengio, Y. (2015). Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. In ICLR 2015.

Dichao Hu (2018). An Introductory Survey on Attention Mechanisms in NLP Problems.

Anna Rohrbach, Lisa Anne Hendricks, Kaylee Burns, Trevor Darrell, Kate Saenko (2018). Object Hallucination in Image Captioning.

Okay, I did not notice them until much later.↩

Not that I don’t speak French, mind you.↩

It was during the holiday season after all.↩

When constructing the references for each predicted translation, I took advantage of the fact that the dataset has multiple target sentences for a single source sentence, so each prediction is evaluated against all available references.↩

This survey paper is a good starting point to learn about the different common implementations of the attention layers.↩