This week I started taking this Coursera class called Introduction to Data Science taught by Bill Howe from University of Washington. Although there has only been one lesson so far, my experience has been quite positive particularly due to the interesting programing assignment, which is to use twitter’s live stream data to analyze tweet sentiment. If you are interested and want to try yourself, you can read the very helpful instruction here and clone the git here (I believe you can access it without signing up for the class, but the course is free anyway). The assignment is given in Python, and, despite a few wrapper functions, students are required to write the majority of the code, which, needless to say, was a very good exercise to me (and to anyone who’s learning Python).

Okay, so much for the class itself. One particular assignment that prompted me to start this project and write this post is the one about estimating the overall sentiment of people from different states based on the messages they tweet and finding the happiest state. To complete this task, we were given a list of positive words and a list of negative ones along with their individual scores indicating certain words are more positive/negative than the others (the lists are included in the git). Then for each tweet, we were asked to calculate the total score for it based on the matches from the 2 lists, and sum up all the scores for each state to determine the “happiest” state corresponding to the highest score. A pretty simple idea, and it turns out you can do a lot of interesting research based on this approach (or some variations of it), and draw a lot of good insights from it. For example, the course website links to this research performed by researchers at Northeastern and Harvard University, which shows the mood of the Americans throughout a day. If you don’t want to read the whole thing, at least watch this video they made showing the mood evolvement. It’s very, very interesting.

Therefore, I decided to do something similar myself, and because I’m very into R Shiny lately, I made a web app showing the realtime changes in sentiment using the twitter live stream data. And here it is (it’s a bit slow to open):

https://runzemc.shinyapps.io/sentiment/

Essentially, the app looks for geocoded tweets originated from the U.S. every 6 seconds and collects them for 5 seconds. Then it parses them and extracts the state information (based on the embedded coordinates) and the tweets themselves. A simple algorithm is run to calculate the sentiment scores, which are finally aggregated on the state level and are charted. 3 charts are made (using ggplot2): 2 showing the mood evolvement on a U.S. map and 1 showing the changes on a line chart (screenshots are attached below).

Methodology

Thanks to the awesome streamR package, I was able to collect tweets easily and keep the whole project in R (yay!). What I particularly appreciated is its parseTweets function that quickly parses out the json data and stores the result in an R data.frame (how nice!). Furthermore, to restrict the tweets to only those tweeted by English-speaking Americans (the positive/negative dictionary is in English), I used the filterStream function and set the coordinate range to (-124, 23, -67, 50), which should cover all the lower 48 states (if it doesn’t, well, I’m not from here).

Speaking of coordinates, to translate them to state names, I referred to this stackoverflow post and used the spatial mapping provided in the sp package (in the Coursera class, we were instructed to not rely on any online sources, so here is the algorithm many of us used instead to determine if a point lies within a polygon).

To estimate the sentiment scores, I found this tutorial particularly helpful. It covers 3 approaches and I picked the first one (note that the R sentiment package mentioned in the 2nd method is no longer available). The simple algorithm, presented by Jeffrey Breen, counts all the positive and negative words within a tweet and subtracts the latter from the former to derive the sentiment score. You can download the dictionaries of positive and negative words it uses here and read Jeffrey’s sample R code here. Note this is a little different from the method introduced the Coursera class in that we are not assigning any scores to the words themselves; instead, we are simply counting the occurrences. If you want to take into account the different sentiment of the words used, you can easily expand the algorithm to do that as well (with a different dictionary).

After calculating sentiment scores for each tweet, we now need to aggregate them on the state level (or any other level you desire to). In the Coursera assignment, we are instructed to simply add up all the scores originated from the same state. However, that depends on how many tweets per state one gets. Because we are not getting the equal amount of tweets from each state (we are simply collecting whatever tweets people has just tweeted in the last 5 seconds), we may run into issues where we get erratic and unrepresentative results based on the small sample size for certain states (e.g., a very grumpy person might be the only one from that state that tweeted). Therefore, we need to scale the scores somehow. Here is my approach:

overall sentiment in state 1 = sum of positive scores / sum of all absolute scores

To illustrate, if we received 3 tweets from a state and the sentiment scores for them are -1, 0, and 2 (0 being neutral). Using the above formula, we get an overall sentiment of 2 / 3 = 0.67, showing a slightly higher sentiment than neutral due to the tweet that scored 2. If we simply averaging over the 3 scores (either including or excluding the neutral tweet), the result we get is still not scaled and may vary a lot from state to state, whereas the good thing about using a percentage approach as shown above is that the result is bounded within [0, 1], with 0.5 indicating neutral. Another thing I tried is discard the scores themselves and just divide the number of positive tweets by the number of non-neutral tweets. It’s slightly simpler but I don’t like that it discards the sentiment scores in total. The result did not differ that much though.

Charting

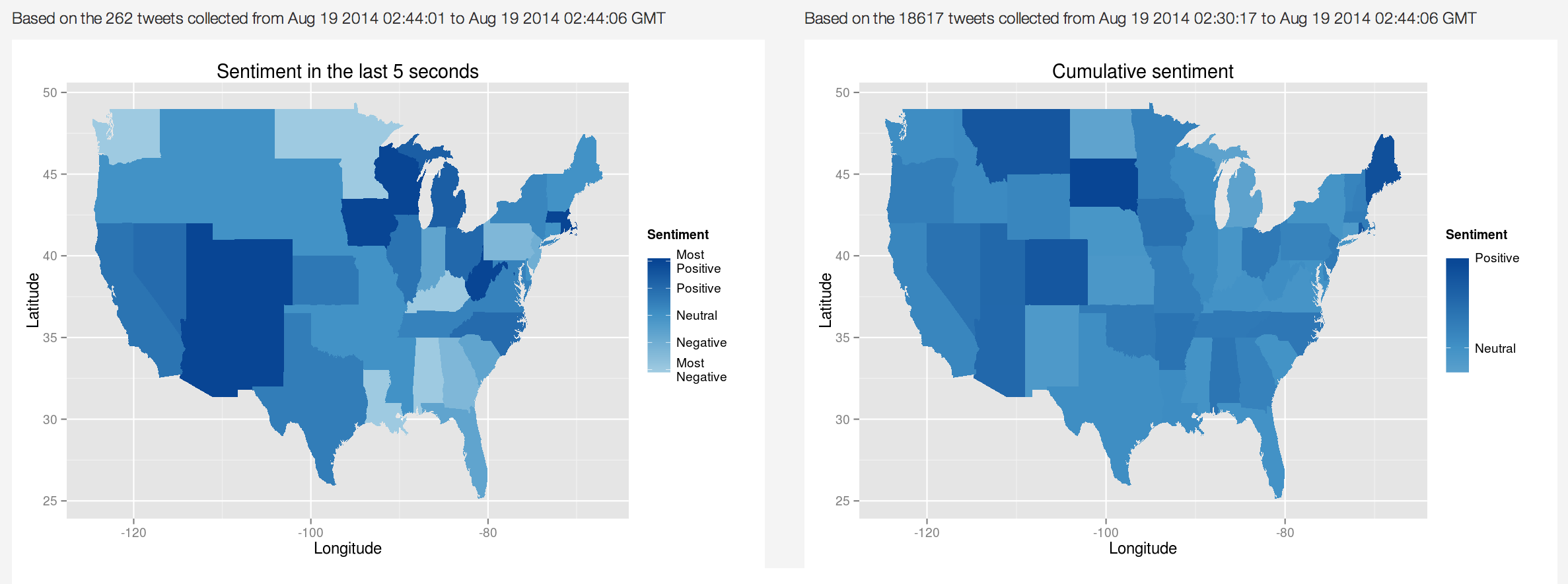

Now we have all the data to present the results. I first created 2 heat maps showing 1) the sentiment changes in the 5-second interval and 2) the cumulative sentiment calculated with all the tweets gathered so far. Below are the 2 charts after I had it run for 14 minutes:

The cumulative chart is more immune to the small sample problem and it gives a nice stable picture as the anomalies are gradually drowned out. As a result, you can see what states are really happy (I’m moving to South Dakota). However, it doesn’t show any fluctuation of the moods throughout the time, which the left graph does. To be honest, the 5-second interval may be a bit too short to generalize (I get on average 150 tweets per each interval), but for web display purposes, a longer wait period may bore the users instead.

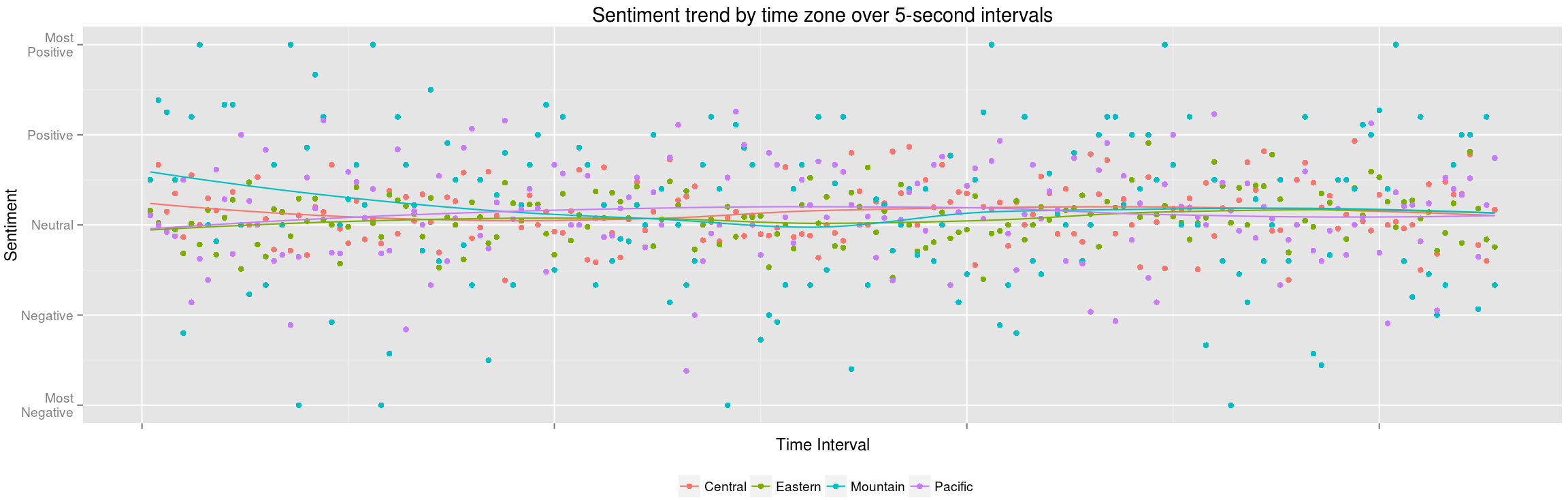

The drawback of the 2 charts above is that it doesn’t explicit show any historical movement. Therefore, I made this line chart in addition that plots the scores calculated using the tweets collected in each 5-second interval (i.e., all the data that are used to make the chart on the left above). Instead of charting them on the state level, I decided to chart them on the time zone level instead hoping to futher reduce the noise and see how the mood changes for people who are all at the same time of a day. However, this is to ignore the interstate variance within a single time zone. Below is the result after I let it run for over 30 minutes:

The loess-smoothed lines are shown along with the raw data points to indicate the general trend. It seems that, despite a few small swings, the trends are generally flat and centered around the neutral. This may be due to 1) the short time period (it is unlikely to see a big overarching mood swing within half an hour), 2) the sample size (not all the tweets are geo-coded; in fact, I think only a small amount are), 3) the way I estimate sentiment scores for individual tweets and the whole region, and/or 4) the neighborhood size that loess takes to build the weighted regression model (the default span value of 0.75 was selected). Due to the limitation of the live web app, I’m planning to rerun the analysis but first collect all the tweets for a whole week (excluding late nights and early mornings). Hopefully, I can get some cool clear trends like those shown in the research linked above.

Finally, a technical note: to automatically pull and update data after a set interval, I used Shiny’s reactiveTimer and autoInvalidate functions. You can see an example in this stackoverflow post here.

Stay happy!