Lately, I’ve become very interested in text mining and topic modeling, and have played around with some popular algorithms like LDA. However, so far my projects have all been centered around what I can learn from a giant chunk of texts and usually stopped after I extracted some revealing and, if I’m lucky, thought-provoking topics from them. In other words, what I’ve been doing so far is all inference but no predictions. Hence, I’ve been toying with the idea of taking it to the next level by applying the topics and knowledge the model learned to future problems, and the idea that interested me the most is to use them to build a recommending system.

To me, it is truly a fascinating application. I still remember the amazement I felt when I first discovered Pandora and, even earlier, last.fm radio. Now as I learned more about it, I have developed a more concrete understanding of how the system works. To my knowledge, there are two main approaches towards building such a recommender, one is gathering as many attributes about the subject as possible, which, in the case of music, may include genre, years, and frequency and, in the case of artwork, may mean style, colors, pixels, and patterns, and clustering them together based on common attributes; the other approach is collaborative filtering, i.e., recommending items that other people, who showed interests in the same items that you enjoyed, expressed interests in. Per my understanding, Pandora took the first route and Spotify initially took the second but is now actively developing the first too because the problem with collaborative filtering is that you place a whole lot of faith on the tastes of your users, which inevitably limits the variety and potential to discover new materials. Besides these two machine learning-based approaches, there have also been many alternatives that rely on human curators entirely. Songza, for example, has a group of in-house music experts that make playlists all day and 8tracks has its users make and share playlists themselves. After trying both, I have to say I do enjoy the human-crafted playlists a lot more than the machine-generated ones. I think it’s because taste is a complex thing and many of us have drastically different tastes when it comes to different subjects. Hence, it may be too difficult to have a machine learn and adapt to the whimsical nature of human tastes.

But it’s still a very interesting problem nevertheless! As my first attempt at building such a system, I made a simple book recommender that, based on LDA modeling results and cosine similarities, recommends books from New York Times’ and NPR‘s lists of bestsellers and from Goodreads’ list of ‘Books That Everyone Should Read At Least Once’ for users. You can check out my app here and my R code here. Below are the process and methodologies I used to create it.

Scraping New York Times

New York Times provides a handy API to query its weekly bestsellers since June 2008, with a daily usage limit of 5,000 requests. In my case, the first step is to get a list of available “list names” such as “the best-selling hardcover fictions” or “the best-selling paperback nonfictions.” There are 37 lists in total and I picked 6 of them. These 6 lists are ”hardcover-fiction,” “hardcover-nonfiction,” “trade-fiction-paperback,” “paperback-nonfiction,” and ”e-book-fiction,” “e-book-nonfiction.” For each of these lists, I retrieved all the information associated with the books that have appeared on them from June 2008 to October 2014, which amount to 440 unique books in total (some books may appear on multiple lists and for multiple weeks). The API is pretty easy to use, which makes the whole process painless.

The API provides a short description on the book itself but it’s usually only one sentence long. As for the genres, they were usually lumped into broad, generic categories like fiction. Hence, to get a more detailed and verbose narratives for a book, I opted to use the descriptions and genres listed on Goodreads. For each book, the website usually provides a paragraph-long description and a handful genre tags voted by users (e.g., 1,000 users agreed a book is primarily classical fiction and 500 added that it is also part of the British literature). After looking each book up using its ISBN number, I pulled all these down using rvest and SelectorGadget.

Scraping NPR

Unlike New York Times, NPR’s bestsellers are selected based on “weekly surveys of close to 500 independent bookstores nationwide,” and since I’m a sucker for anything “independent,” I simply had to get it. Also a training set of 440 books alone are just too small. There is no API to crawl these bestsellers, but the website is clean enough to scrape easily. By pulling down the bestsellers going back to 2012, I added an additional 541 books to my training set.

Similar to books from NYT, I’ve also retrieved the descriptions and genres for them from Goodreads. Since the books from this list don’t come with ISBNs, I had to look for them using the book titles and author names as keywords. Based on my experience, using this simple approach did return the correct books most of the time.

Scraping Goodreads’ most recommended books

Initially I just stopped at the 2 bestsellers and went with those, but during testing, I found a lot of these books, although widely sold, are not legitimately good books (e.g., I cringed every time I saw Twilight being recommended). Hence, I spent some time looking for additional books that can complement my little repertoire and eventually found this very helpful list from Goodreads called ‘Books That Everyone Should Read At Least Once’. Although, sadly, Twilight is still there, my training set got a big boost on classical literature, which is a big hole I found in these lists of bestsellers.

The list has over 10,000 books and when I tried to add them all, I found the performance suffered significantly. Also many of these books, at least their descriptions, were written in foreign languages, which adds an extra layer of complexity in topic modeling. Hence, I cut them down by keeping only books that are written in English, have an average user rating above 4, and have a ranking within the top 50%. Doing so narrows the total number of books down to about 2,000.

Mining genres using LDA

With about 3,000 books in total, I was finally ready to do some topic modeling. On my first attempt, I didn’t use any sophisticated topic modeling techniques like LDA. Instead, I simply mined the descriptions of all the books together by creating a giant document-term matrix with each document representing a book, and when a new book is entered by a user, I constructed a single-row DTM for it and computed its cosine similarities with the training DTM. The corresponding books with the greatest similarities are seen as those that are the most similar in style with the new book, hence producing valid recommendations. However, as it turned out, simply relying on the descriptions alone yielded a lot of false hits. As an example, when I tested with the book The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, one of the top recommended books I got is a scientific study on birds, which has absolutely nothing to do with the book itself. Hence, I found it necessary to cluster books per their genres first and this is when Goodreads’ genre tags came in handy.

If you use Goodreads, you’ll notice that its genre tags are very similar to the topics obtained from an LDA model in that one book can be associated with multiple tags, each of which are associated with a number of votes cast by users, indicating their consensus on a particular categorization. Therefore, an LDA model that allows the coexistence of all the genres tags seems a natural choice. To take advantage of the votes, I repeated each tag by an amount that is proportional to the number of votes it received. For example, if a book received 1,000 votes on fiction, 100 on mystery, and 10 on Asian literature, I would repeat each of the 3 tags by 100, 10, and 1 times, respectively, to emphasize the “dominance” of each bucket. As a result, when an DTM is later created using this book, the frequencies for the 3 terms would be 100, 10, and 1 instead of 1 for all of them. The goal of this artificial inflation, in this instance, is to distinguish the book from books that have the same 3 tags but with substantially different weightings (as determined by the votes) so that they won’t be grouped together. In doing so, I was hoping to add more emphasis on the genres themselves to improve clustering accuracy.

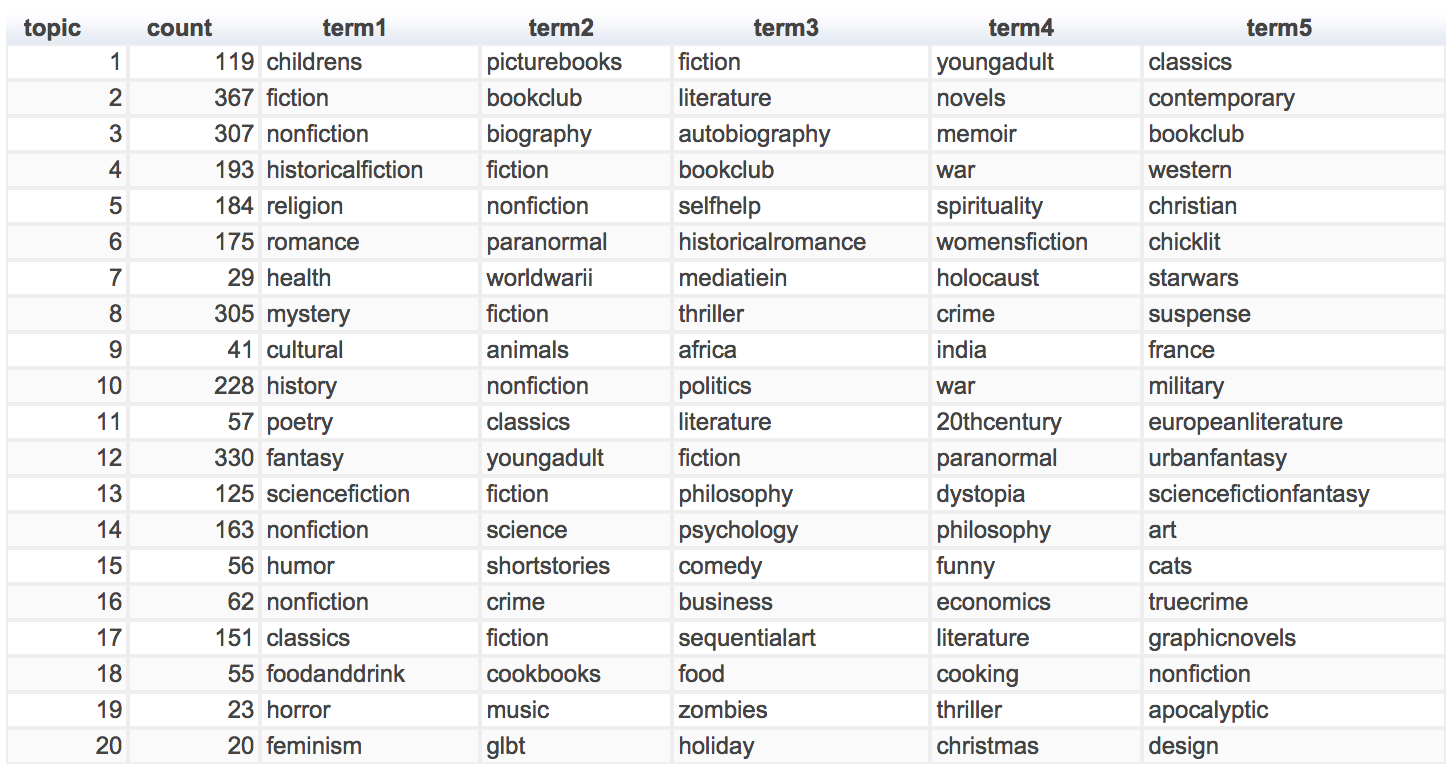

After constructing such a “weighted” DTM, to determine the optimal number of splits, I ran a bunch of LDAs on it and found 20 sufficient to summarize most, if not all, of the genres. These 20 topics, along with their top 5 tags and the number of corresponding books, are illustrated below:

It seems that the model did a decent job at separating general fiction from nonfiction, and adequately distinguished between modern and classical literature and biography and popular science. However, when it comes to digging deeper into the themes or topics, it was sometimes confused by some specific terms used. For example, it grouped World War II and Star Wars together due to the common use of the tag “war,” and, for some strange reasons I’m still not quite sure of, it put them together with “health.” I guess such phenomenon is partly due to the use of tags with specific references (e.g., “young adult historical fiction”), which makes it harder for the algorithm to find common themes. In fact, based on the perplexity curve generated using a number of topics, 20 is not really the optimal split as the perplexity metric continues to decrease after 20. I had to stop at 20 because going further would leave certain buckets with too few books. At this time I’m still tinkering the genre tags and experimenting new ways to cut and group them more accurately.

Cleaning descriptions

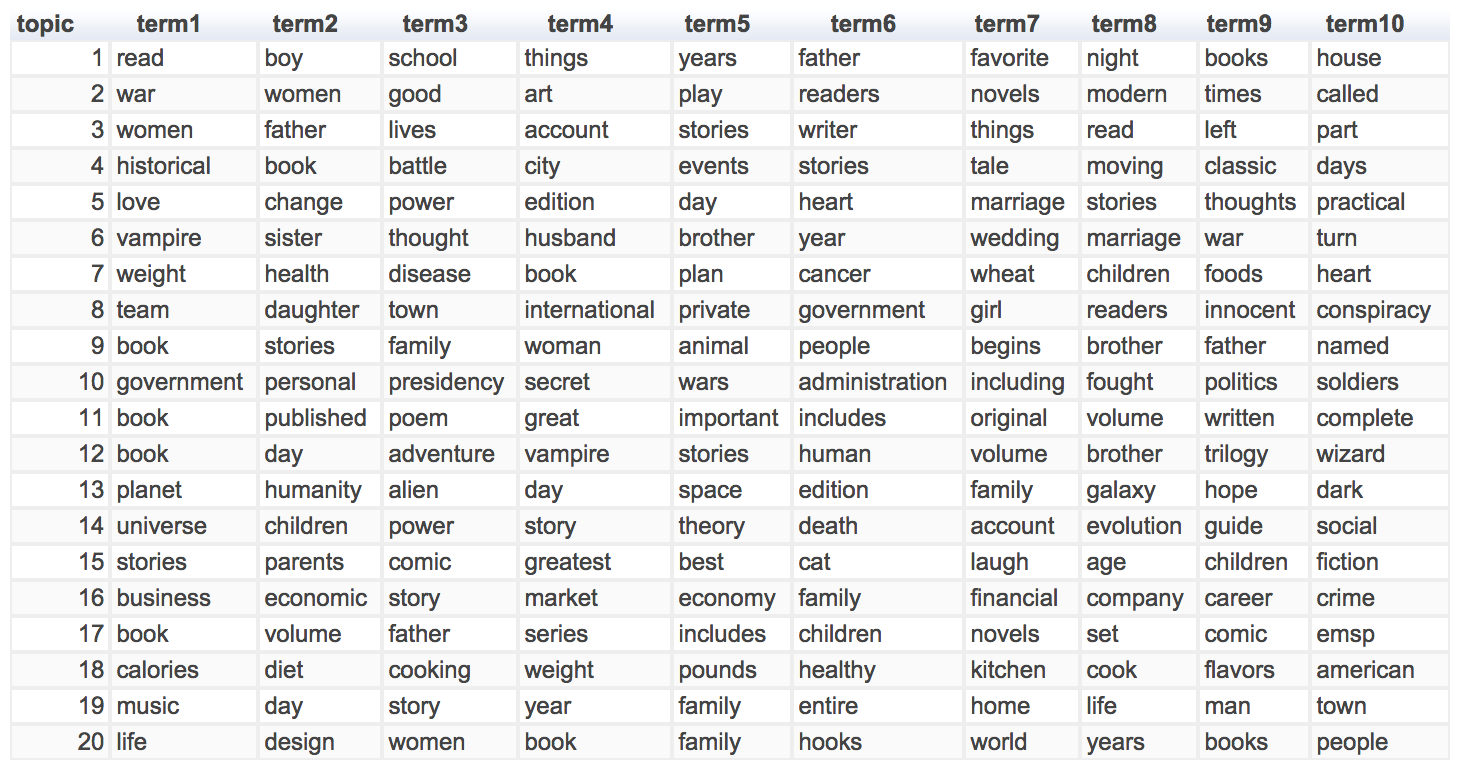

Matching a new book to a particular genre bucket is the first step of recommendation. What comes next is to compare its description with those of all the books put in that bucket based on the modeling result above. Before comparing the descriptions, we need to clean them first. To do that, I simply kept all the alphabetic characters and ran a part-of-speech tags on them and only kept adjectives, nouns (but not pronouns), and verbs for each description because, based on my experience, these words best describe a book and more words may introduce noise. After removing these extra words, each book has on average 64 words to describe them. Out of curiosity, I extracted the top 10 terms used to describe the books of each genre and here are the results:

By comparing it side by side with the genre table above, I did find some interesting patterns and common themes. For example,

Women surpassed men in contemporary literature and biographies (as in groups 2 and 3),

When it comes to religion and spiritual books, love is the universal theme (group 5),

Vampires clearly dominate the romance and fantasy novels (groups 6 and 12),

Weight is widely discussed in health-related books (group 7),

Little girls seem to always play a big part in thrillers (group 8),

The universe and children are the focus in popular science (group 14),

Cats, despite its grumpiness (sorry), are favorite subjects in funny stories (group 15),

Ironically in cookbooks, calories and diet are the most mentioned aspects and flavors come way later,

Horror stories usually involve a whole family.

Recommending books

Now with genre buckets and cleaned descriptions, we can finally take our model to a test run with a new book! This process is described as follows:

When a user enters a new book, first look it up on Goodreads based on its title and author, and find the first result that matched the two attributes.

Go to the book’s profile page and pull down its genre tags (along with their votes) and the description.

Apply the genre LDA model to the book’s own “weighted” genre tags and determine the best 2 categories that fit the book based on the posterior probabilities (based on my experience, the top 2 categories are often sufficient to summarize a book’s genre).

Determine the number of nearest neighbors to draw from each category based on the 2 probabilities. For example, say we are planing to recommend 10 books in total, and based on the model result above, the top 2 buckets are associated with the probabilities of 0.8 and 0.2, respectively. In this case, we’ll draw 8 books from the first bucket and 2 from the second.

Clean the description of the book, and calculate the cosine similarities between its description with those of all the books from the 2 groups determined above. To calculate the metric, first construct a DTM matrix using the corpus made up of the descriptions, and use TF-IDF to remove terms that are either very infrequent or very common across all documents.

Rank the resulting similarity metric in descending order, and find the most similar books up to the amounts determined in step 4 (e.g., 8 from the first and 2 from the second), and recommend these books to the user.

Profit.

Now let’s try 2 books: one fiction and one non-fiction, and see how the recommender does.

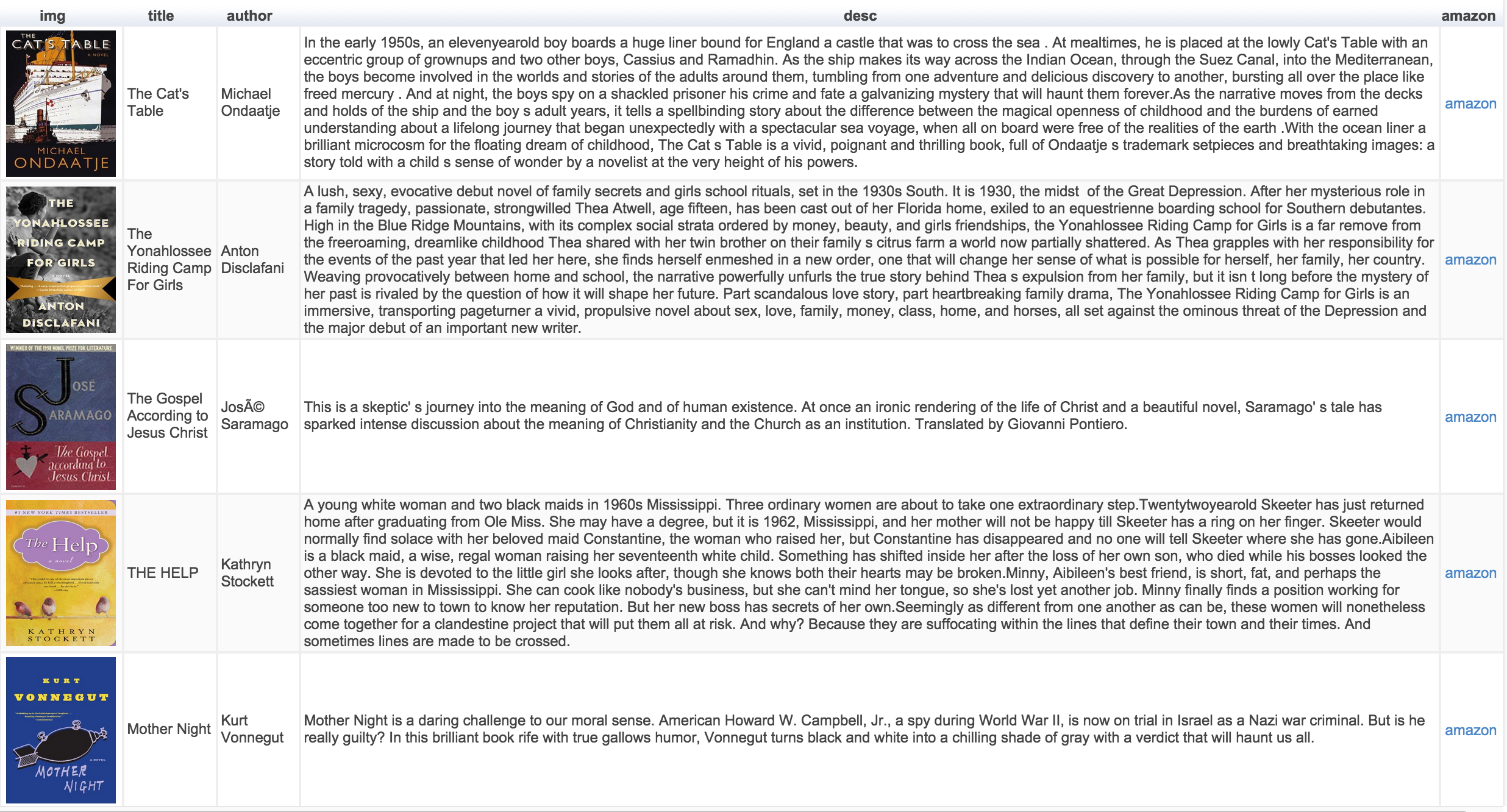

For the fiction, I chose the last fiction I read – Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, and these are the recommendations I got (due to space constraint, only the top 5 recommended books are shown):

It seems that the recommender has picked up themes such as friendship, secrets, and coming-of-age. However, with the exception of the first book, I wouldn’t recommend any of them to someone who enjoyed the book at issue. It’s not that these are not good books, but they are just not directly comparable in my opinion (especially the religious one). This is actually a common mistake I’ve seen while testing the model because, by relying completely on the limited words used to describe a book, the themes it can discover is simply too superficial. What’s worse, to avoid any spoilers, some descriptions are too cryptic for the model to make anything out of them. Hence, as interesting and ambitious as it is to mine the descriptions, I think the focus should still be on the genres themselves. In absence of a more thorough description, classifying a book under the right category with enough granularity should complement the lack of specificity in the description.

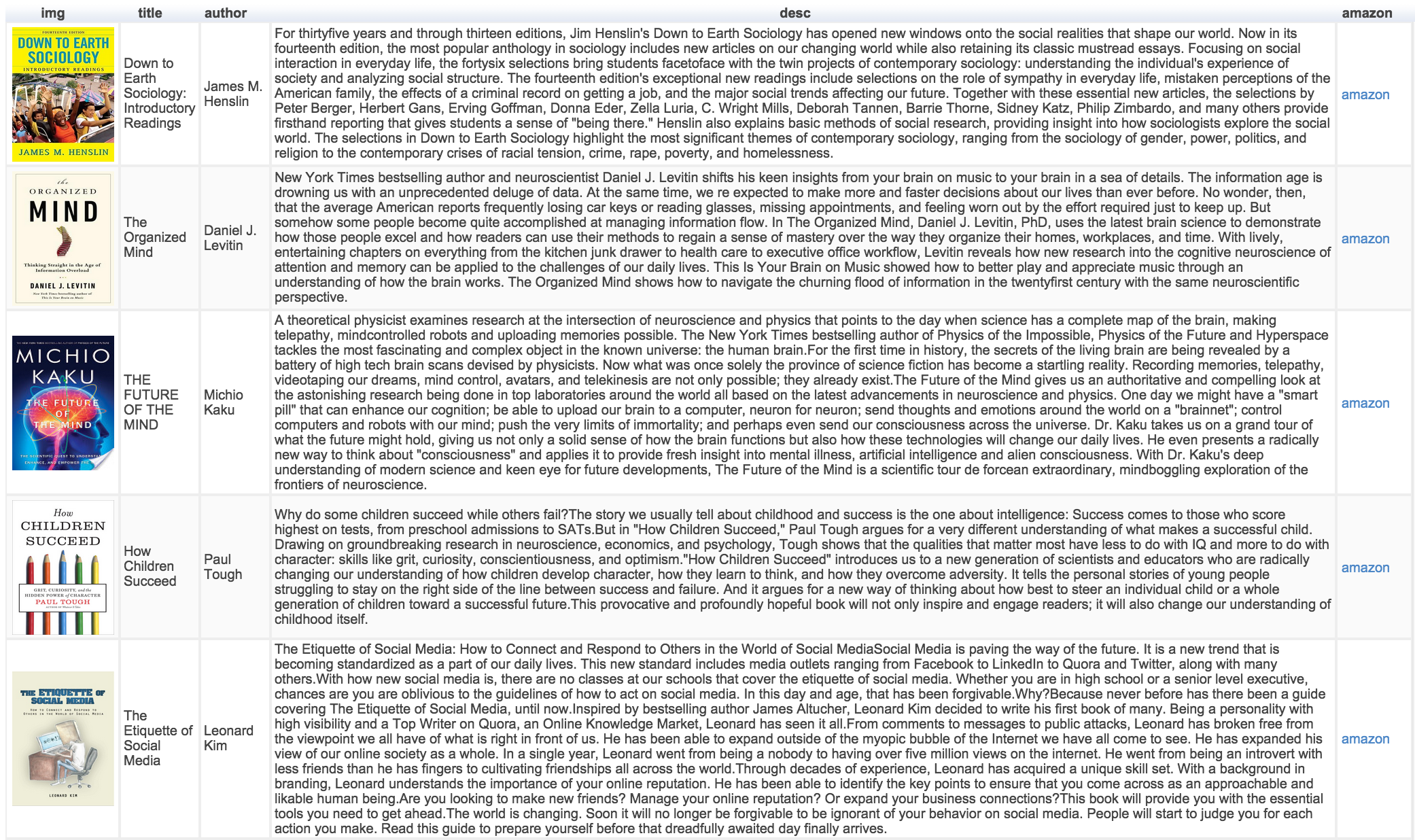

Now let’s look at nonfiction. Once again I picked the last nonfiction I read – The Social Animal, which, by the way, is a very enlightening and fun book. Using that, I got these books in return:

I am much more happier with the results this time as it successfully picked up the sociology and psychology themes, which is kind of expected since it’s often easier to describe a nonfiction than a fiction and one runs into less trouble of taking words as is.

Conclusion and future work

In my first attempt at making a book recommender (something that I’ve always wanted myself), I relied on the LDA models based on the genres and the cosine similarities between the descriptions of books. The result, although promising, still needs a lot of improvement as some of the matches it found are suboptimal. There are 2 things that I see I can do to potentially boost the performance: one is to fine-tune the genre breakdown, possibly, obtaining additional opinions from other sources, and two is to somehow get more descriptions on these books, especially for the fiction. One potential source is Wikipedia as it usually includes a full plot description and critics’ reviews.

That’s it. Read more!