If you are not from China or living there, you are probably not familiar with the term 八零后, or post-80s, but if you are, like me, I think you’ll agree that this is probably one of the most widely used and abused terms in modern China. Quite literally, it refers to Chinese people who were born in the 1980s (me included) and the reason it gained so much attention and exposure as compared to, say, 九零后 (post-90s) or 零零后 (post-00s), I think, stems from the fact that our generation has simply seen and been through way too many things that have never been seen or experienced by prior generations and are simply taken as norms for later ones. Without digging into history too much, most people would agree that China’s massive modernization began in 1979. Although started with literally very little, it picked up impressively fast, which made the following two decades quite iconic in terms of revolutionary changes: higher education resumed, factories were popping up everywhere, western civilizations were assimilated, and, most importantly, people were getting rich. Growing up in such a time, we were constantly reminded how fortunate we were simply for having all these things (although I doubt, being kids, we really wanted any of those ourselves). In the meantime, technology soared, and, overnight, we traded the toys and games our parents and their parents played for generations for computers, MP3s, cell phones, and, most prominently, the internet, which, I think, is really the tipping point where we accelerated past our parents and permanently left them behind. Suddenly, we didn’t want anything our parents had wanted and we couldn’t understand and fathom how they lived a big portion of their lives like they did. We saw on TV, movies, and the internet how westerners lived and decided that was a far more liberated way and wanted the same things too. And, soon enough, we _got_ all those things. Being young and, shall I say, virtually westernized, we welcomed all these changes with open arms and quickly grew accustomed to them, but the same cannot be said about our parents. Although for the material things, they eventually caught up, they were not so quick or keen in adopting the new mindset, hence creating a deep clash between the two generations. One of the biggest conflicts is the attitude towards marriage. For many of our parents, marriage is just something you would do at a certain age, just like starting to work or retiring. They don’t understand why it’s so different and complex for us. They think we’ve seen too much and thought too much, which complicated everything for us, including something as simple as getting married. Naturally, as higher education becomes more accessible and people become more ambitious, familial matters like this simply get pushed back.

But with all these changes, are we really a better generation? One commonly-acknowledged flaw in us is materialism, which to be fair is not only affecting us (if that offers any consolation). For example, I don’t know what’s with us Asians, but we are just obsessed with electronics. iPhones, a $700 piece of hardware, have ridiculously become a status symbol, so much that a new model is being sold at more than twice the price in the black market. Riding a train in a metropolitan city, you’ll be surprised at how many people are looking at their phones the whole time (despite what an exciting piece of device it is, all of their owners look bored) and it’s almost impossible to find anyone reading a book for a change (yes, they may be reading ebooks, but my personal observations have found that very rare). Electronics aside, social medias are filled with pictures and gossips about celebrity (many of whom are foreign), selfies, and cynical comments about the society (which is a whole other topic on its own). Perhaps most ironically, when browsing the profiles of people from my generation, I keep getting a funny feeling that, despite great promises, we are becoming our parents after all. And we thought, or even vowed, that we are going to be different.

Given all these contradictions, the post-80s are undoubtedly a very interesting generation and have been extensively studied by both the Chinese and western scholars. Being one of this group myself, I wanted to take a closer look at ourselves as well. My tool for this study is Weibo, China’s microblogging service, which, according to wikipedia, has more than 500 million registered users, which is almost half of the Chinese population (part of its popularity is due to the fact that Twitter is blocked there). The obvious advantage of using that is the massive sample size (again, according to wikipedia, about 100 million messages are posted on it every day), and the biggest downside is that the messages are written in Chinese, which poses a big challenge in text mining (described in detail below). Also, due to its popularity, many businesses, e-commerce most prominently, have active accounts there and use them to sell products. Hence, to get an accurate picture of the mentality of the young people, we need to weed out these business accounts. Moreover, many of the messages are not expressions of original opinions but retweets of other people’s voices or news. However, this is not really a big deal since seeing what people share can paint a good picture of what they care about as well.

So here we go.

Scraping Weibo

Like Twitter, Weibo provides an API that can be used to retrieve user information and their messages, but like most APIs, it has a throttle limit that requires careful monitoring and economical requesting. Because I knew the limit would certainly not be enough for my trials and errors, I opted to write my own program to crawl its data. The tool I used is Python, particularly the module selenium that uses web drivers like Firefox to navigate websites automatically and obtain page sources, which can then be parsed using tools such as BeautifulSoup. The advantage of using such a web driver over a headless request through, say, urllib2, is that you get to simulate a more human-like way of browsing as you can direct it to send keys to a search box or press a button to go to a new page, and, importantly, wait until a page is fully loaded to proceed to crawl the page source, which is particularly necessary when dealing with javascript-enabled websites. Also many websites have taken means to detect and block robotic requests, hence using an actual browser can usually avoid such blocking, although adding a header to urllib2 requests may also work. Shortly after I finished this project, I found that the whole scraping process can be done in R too using RSelenium and rvest, the latter of which is a new package written by Hadley Wickham and is, in my opinion, easier to use than BeautifulSoup. How convenient!

Since we can’t possibly get tweets from all 500 million users, the first step is to decide which users to “target at.“ To do that, I used Weibo’s search function, which, as shown below, allows one to specify a bunch of criteria, including location, age, and gender, to find a set of users that meet these criteria. Each requests return 50 pages of users, which amount to 500 users in total.

The page requires you to specify at least one criteria, hence, to maximize the number of users I can get without going overboard, I looped over all the provinces available while keeping other criteria except age unspecified. To keep my subject the post-80s, I restricted the age to be between 23 and 29. This way, I got 17,000 users in total.

But it doesn’t mean I can use them all because, as mentioned above, many of the Weibo users, despite having a valid age and gender, are actually business in disguise. To filter out those accounts, I used the number of followers as my measure given that most of those accounts have an unusually large fan base, and kicked out any account that has followers greater than the 25th percentile of the entire follower distribution, effectively reducing my user size by 3⁄4. The resulting user group has at most 2,400 followers and the remaining size was a lot easier to manage when it came to retrieving each user’s tweets.

Using a list of over 4,000 users, I queried another website called Weibo Life, which appears to be a third-party app based on Weibo and pulls tweets from it directly. The reason I opted to use this instead of the actual Weibo website is that this app (or whatever it is) is a lot cleaner to scrape, unlike the real one that is filled with javascript and random links. Regarding what this app is exactly and how that is related to Weibo itself, I’m still not sure as I couldn’t find any useful mention of it anywhere, but I can attest that this little nifty website is pretty robust and, although it may throw out a 403 error once in a while, it doesn’t impose any limit on the requests, and in case of such a 403 error, based on my experience, waiting for 2-4 minutes can generally solve the issue (such a wait upon an error is included in my code). For each user, I tried to get 5 pages of their tweets from the website, which amount to around 100 tweets, along with their regions (because I wanted to test if there was any geographic differences). In the end, I was able to get almost 500,000 tweets in total.

Analyzing data

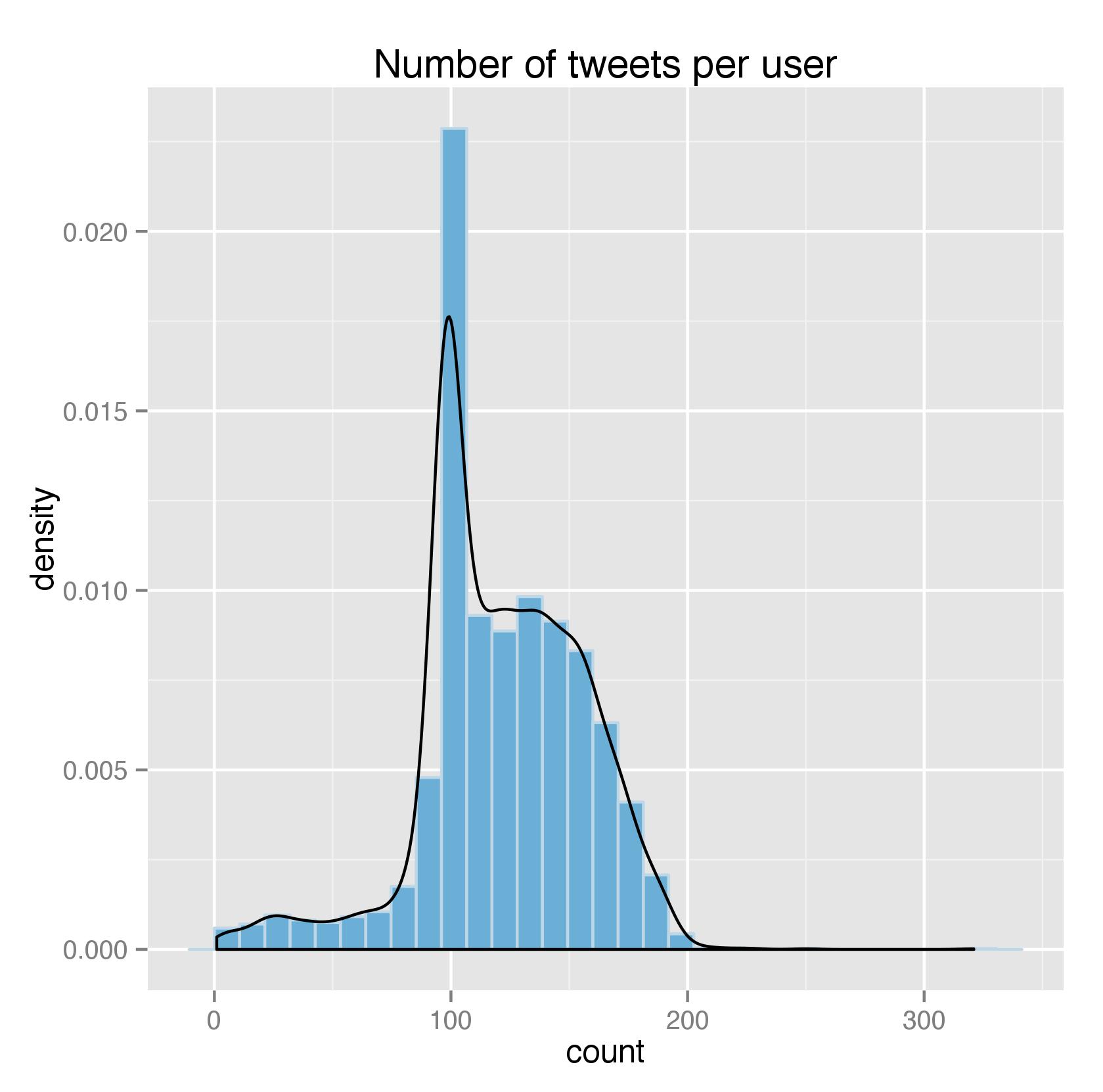

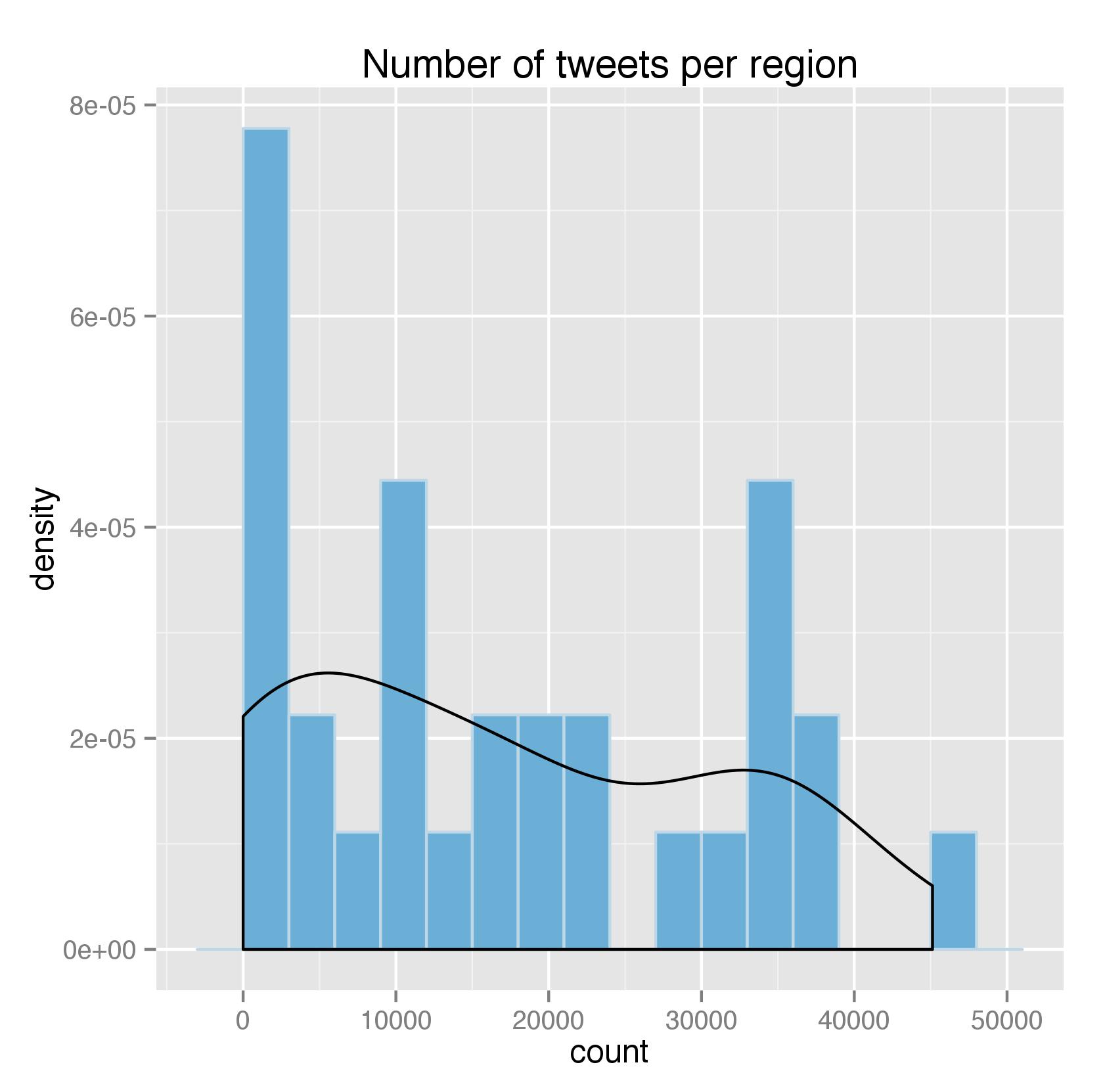

After getting all these data, I switched to R to analyze them (again I could’ve done the whole scraping in R as well). Because I was planing to take all these 500,000 tweets as a corpus and ignore the user-specific factors, the first thing I did was to check if the tweets-per-user distribution is rather normal as opposed to only a few users generated 5 full pages of tweets.

As shown above, although not exactly normal, we don’t have a long tail on the right, indicating most users have an equal voice in our dataset.

Being more comfortable with the data, the next step is to figure out how to mine them. As briefly mentioned above, mining Chinese poses a bunch of challenges. First of all, a simple bag-of-words approach simply doesn’t work here because most of the Chinese words, unlike English, only have real meanings when combined with other words, and depending on which words they are paired with, the resulting combinations may have drastically different meanings (which I always feel shows the superiority of our language :-) ). Secondly, given the large amount of homophones in Chinese, it is not uncommon to see people use the wrong words. What’s worse, many of such instances are not really the result of an honest mistake; instead, they are actually intentional! I don’t know what exactly caused it (part of it may be due to government surveillance), but it is now a fad to intentionally write your sentences with wrong homophones and people will find you cute and funny - what a time we are living in! Given that, I feel it’s almost impossible to mine the Chinese characters posted on the internet in an unsupervised fashion because if you just take each word literally, what you end up with may be way further from the truth than you think.

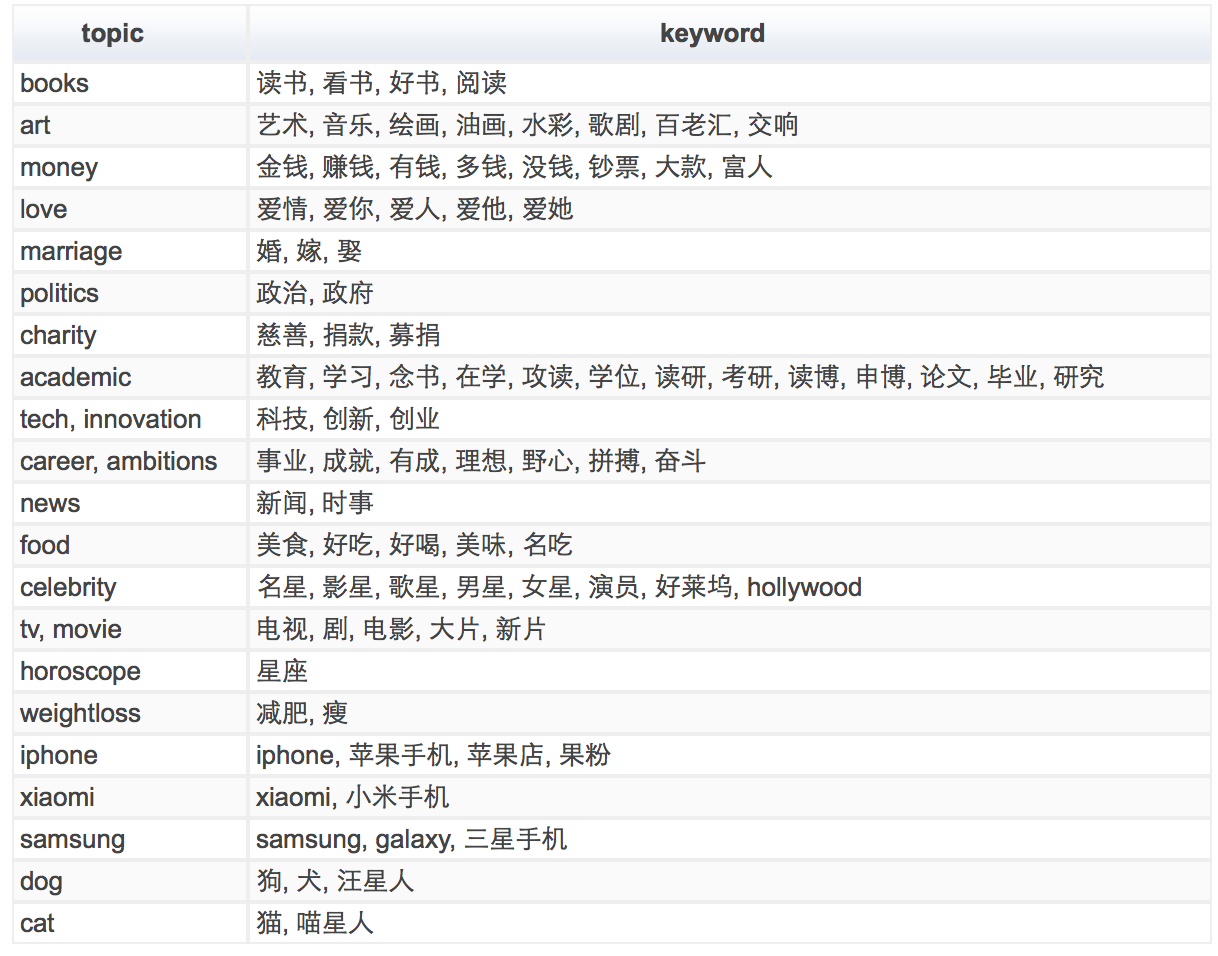

Due to these challenges, to my knowledge, there is not yet a widely-accepted algorithm, not to mention an R package, available for mining Chinese texts yet. Hence, for this analysis, I took a simple route by first defining a set of topics that I’m interested in and brainstorming a bunch of keywords for them (which, based on my review of some tweets, are likely to be used in those topics), and using these keywords to find the tweets that potentially fall into those buckets. Below is a table showing the 21 topics I defined (based on pure curiosity) and the keywords I came up with:

If you read Chinese, you’ll notice that when defining keywords, I tried to avoid single characters due to the reason described above. Doing this may leave out some tweets for certain topics, but my experience of trial and error shows that you can never be too strict - even using these, I still end up with many irrelevant tweets. For example, the word panda in Chinese, 熊猫, is composed of 熊, bear, and 猫, cat (hence, literally bear cat). As a result, using 猫 as the keyword to capture all tweets related to cat will unfortunately also capture a bunch of pandas, and it certainly doesn’t help that panda is a commonly-used emoticon on Weibo, which, when scraped from the website, just shows the text itself. However, eliminating 猫 as a keyword also kicks out the majority of mentions regarding cat since, unlike other Chinese characters mentioned above, you don’t need to pair anything with 猫 to refer to the animal. Hence, without a better solution, I just left it as is and treated pandas as cats.

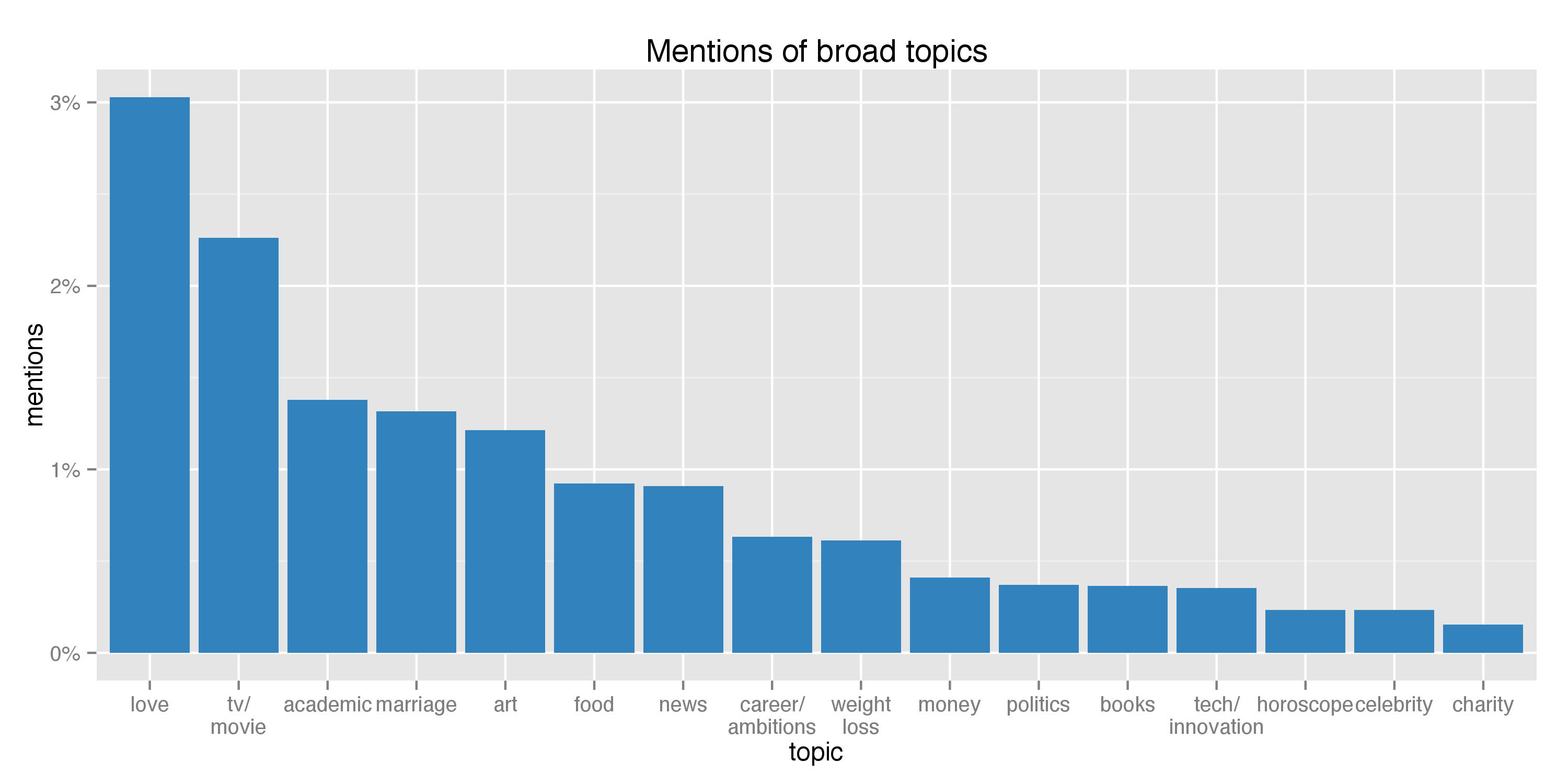

With all the topics and the (imperfectly selected) keywords, I proceeded to calculate the percentage of tweets mentioning these keywords and, thus, roughly pertaining to these topics. First, let’s look at the mentions of the 16 broad topics (stopping before iPhone):

As shown above, love appears to be most universal topic, implying that the post-80s today, being in their mid- to late-20s, spend a lot of time brooding over love. After seeing pages and pages of tweets talking and, most of the time, arguing about and questioning love, I found it not surprising at all. The second most discussed topic, again, is not surprising either given the mass popularity of foreign TV shows, most of which are American, British, and Korean. Interestingly, when it comes to American TV shows, it is usually not the most critically-acclaimed ones that garnered the most attention. Instead, most of the time it’s the minor TV shows that inspired loyal following (think CW). What comes next is academic, which still makes sense considering many of us just finished schools a couple years ago and some of us are still in graduate schools. Finally, there comes marriage, which I had honestly expected to appear even earlier given the whole non-stopping discussions on it and the related topics such as the “left-over women” and the various dating shows. With that, I’ll leave the rest of the topics alone and move on to the fierce battle in the Chinese smart phone market:

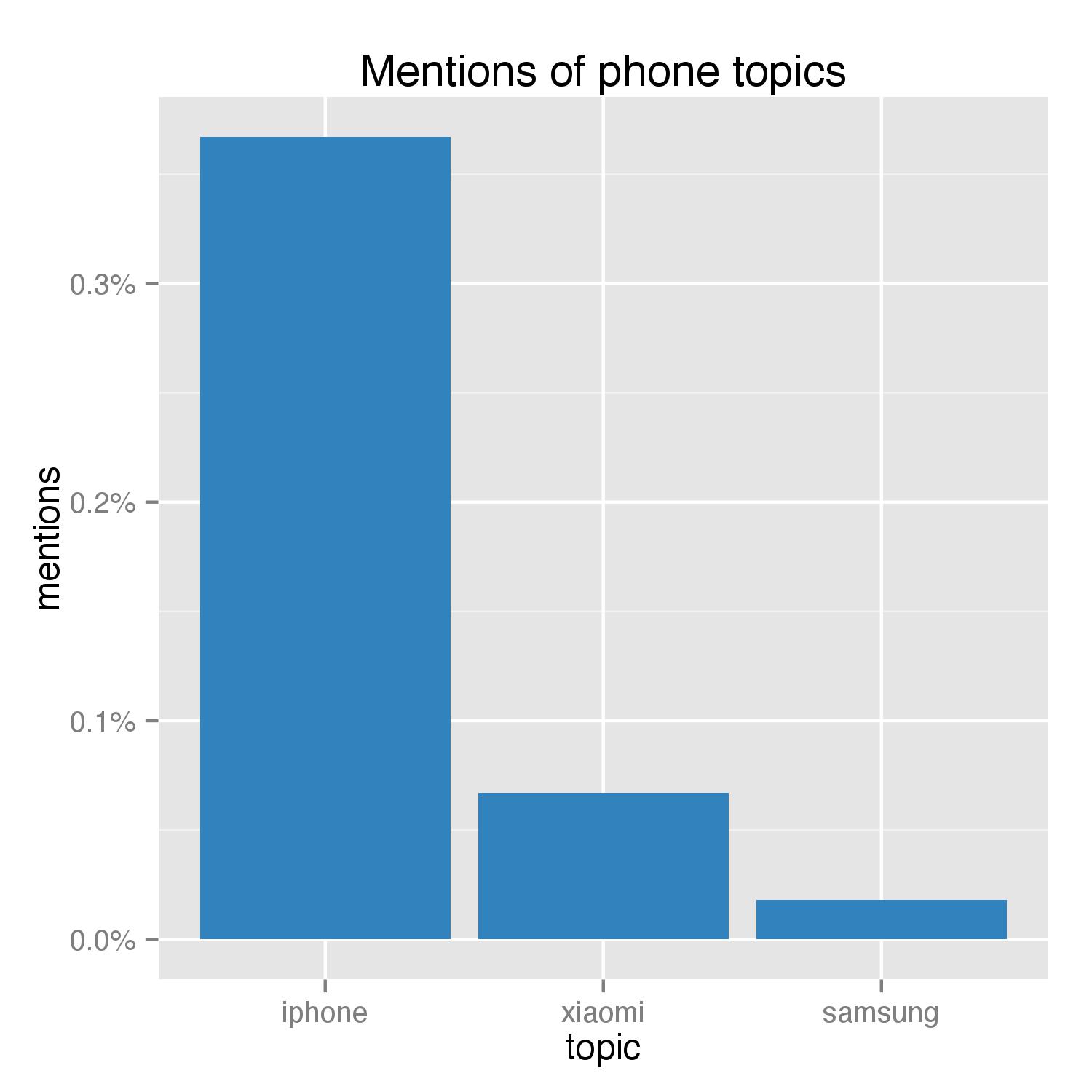

It seems that, despite all the buzz that Xiaomi and Samsung have created, at least based on social media mentions, iPhone is still the king of the smartphones. However, this analysis is possibly biased because I did it right after iPhone 6 went on sale. Nevertheless, Xiaomi, the local high-profile smartphone-maker, certainly surpassed Samsung.

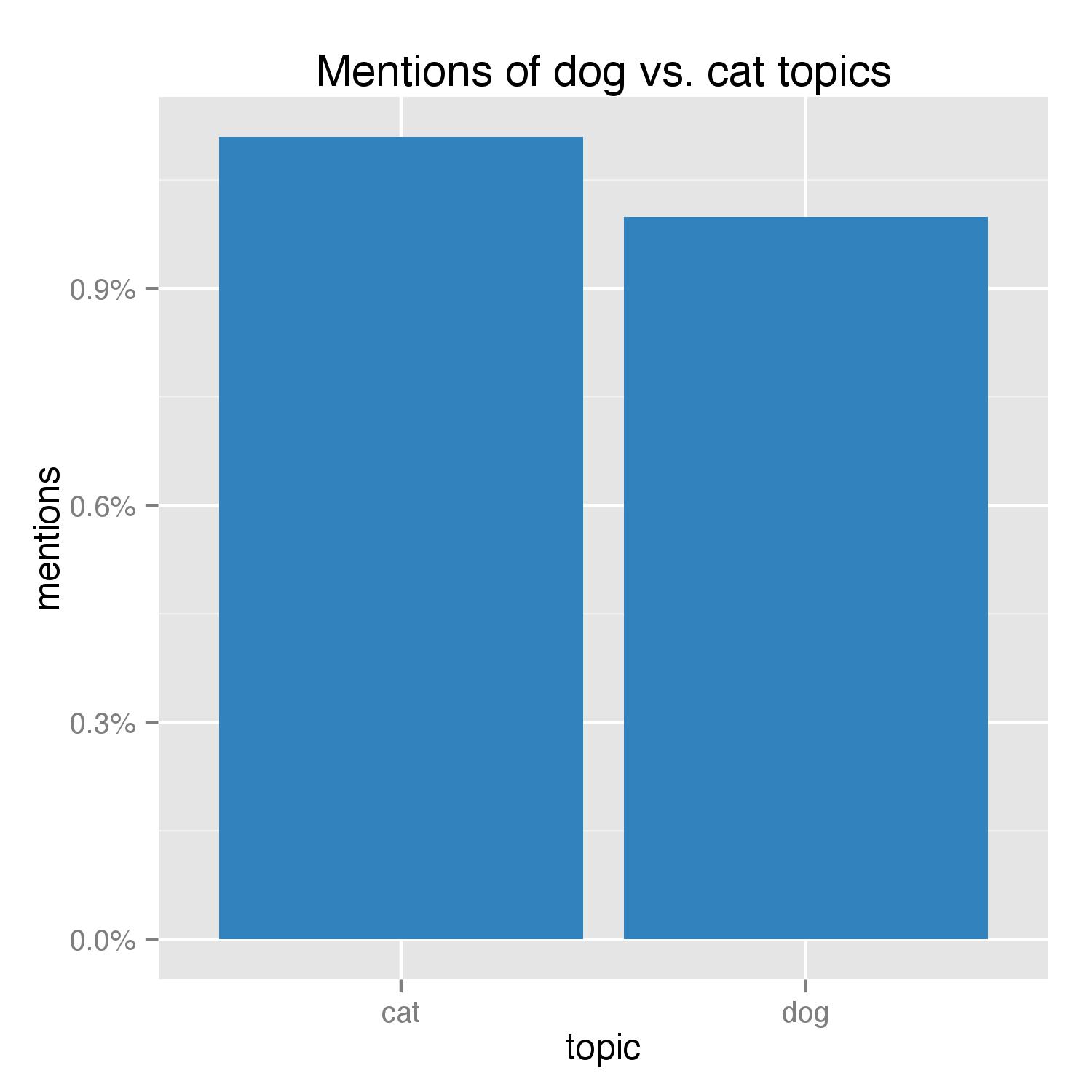

Lastly, let’s try to resolve the age-long battle between dogs and cats to see which are more favored by the post-80s:

Alas, it seems that most post-80s are cat persons! Given the close results, I’m just going to go ahead and say the comparison was rigged because most of the extra cats were impostors by pandas.

After looking at all these topics on the whole, let’s explore whether there is any geographic difference among each topic. However, for some reasons, the tweets I got are not evenly distributed among all regions. As shown below, we have a lot of regions that have 0 or near-0 tweets:

One of the reasons may be that, for those regions, I got mostly business accounts from the search results and hence excluded them in the analysis. To prevent them from skewing the result, I removed all the regions that have tweets less than the 25th percentile and ended up with 22 regions in total.

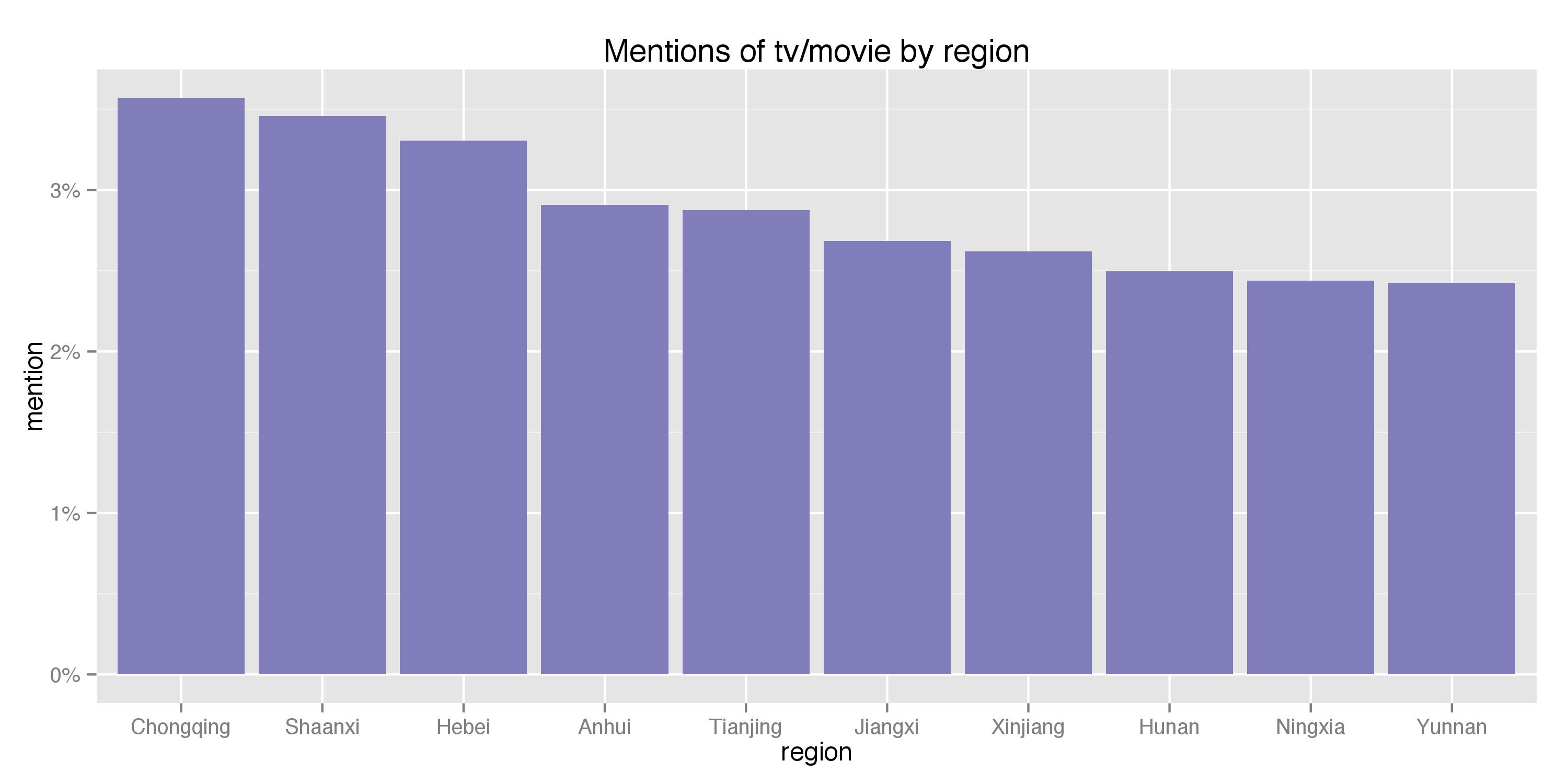

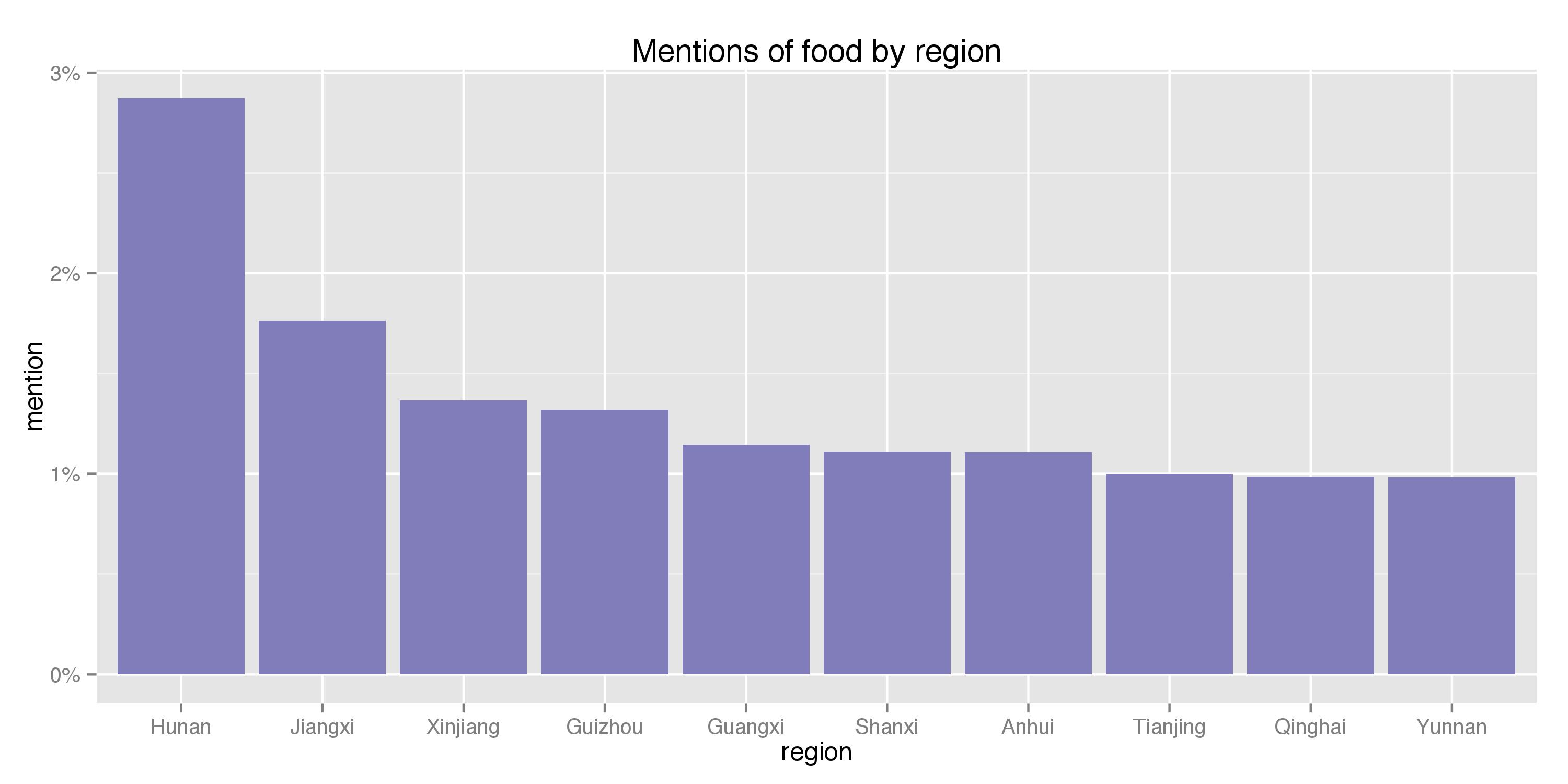

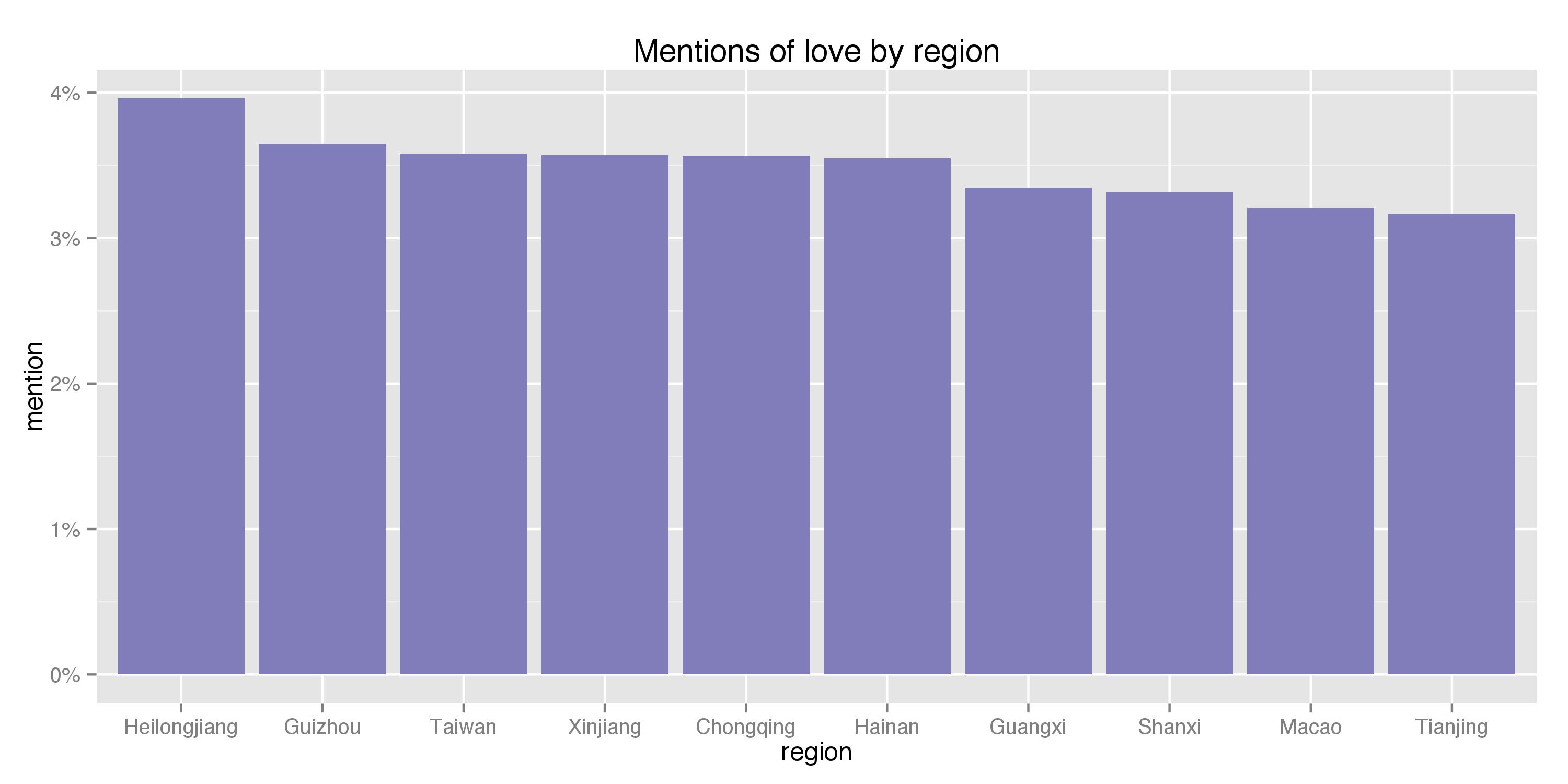

Given that most of these places will show similar topic mentions (because, after all, people from the same generation can not be too different from place to place), I picked the 3 most geographically-diverse topics to present. I identified them by first computing the percentage of mentions per region for each topic, calculating the standard deviation of the metric across all regions, and identifying the 3 topics that generated the highest standard deviations (hence exhibiting the largest regional difference). The resulting 3 topics are TV/movies, food, and, once again, love. Their percentage mentions for the top 10 regions are shown below:

Visually, it appears that food shows the most diverse pattern within the top 10 regions. Specifically, Hunan, known for its spicy food, greatly surpassed the other provinces and seems to have the most foodies. Meanwhile, Chongqing, known for, among other things, its cloudy weather and relaxed lifestyle, watches the greatest amount of TVs and films, and Heilongjiang, being in the far north of China, are the most love-struck (the two are probably not really correlated).

Conclusion

Despite my initial hope to cast doubts on the stereotypes of the post-80s, my analysis seems to confirm them in that it shows that our generation, despite soaring confidence and mounting ambitions, are internally conflicted. We heatedly argue about the meaning of love and marriage and question the necessity and moral of getting married for money, security, or solely for the sake of doing so, but at the same time, we are not immune to materialism and superficiality. We love dramatic TV shows and romanticize the idea of a Korean-drama kind of love, meanwhile, although not shown in the analysis but evidenced in the actual tweets, we are also deeply cynical about the society and the government, but only know how to complain about them. Yet, perhaps, this is just part of the universal mentality of the 20-something going through their Odyssey years across the world. Perhaps I just need to get over myself and quit thinking we are that much more special than anyone else.

† The code for this project (including both the web scraping and analysis) has been uploaded to github.